Early Industries

Milling, Malting and Brewing

Harlow's major function over the centuries has been to provide services to the population of its surrounding agricultural hinterland, but it has also provided the site for a variety of industrial functions, most of them producing for the local market. Harlow Mill served the needs of Harlowbury manor from 1066 until the middle of the 19th century. The buildings which survived after it ceased operation as a mill, most of them dating to the 17th century, were converted to a country club in the 1920s. The buildings over the mill race were destroyed in 1946. The rest of the structure is incorporated in the restaurant.

In addition to Harlow Mill, there were water-powered mills at Burnt Mill, Latton, and Parndon. There were also windmills at Kitchen Hall, on Harlow Common near Foster Street and one east of Churchgate street for the Moor Hall Estate. Latton Mill, operated in the 1890s by Joseph Thurgood who ran a bakery in Broadway (now part of Market Street), closed in 1926 and was demolished, although the locks and water channels which supplied water for the mill can still be seen from River Way, the walking trail on the south side of the canal. Parndon Mill, which closed in 1950, was the last to go, but it got a new lease of life in 1969 when it was converted to an art gallery and artists' studios.

Malt (i.e. malted barley) was an important local product, but its future was in doubt by the end of the 16th century because the malt waggons were forbidden to travel on thertoads at night because of their poor quality. The industry was saved by the opening of the Stort Navigation and by 1745 malt was flowing southward once again to serve the London market. In 1833 there were 100 malt warehouses in Bishops Stortfort, 11 in Sawbridgeworth and 10 in Harlow. One of them was Reed's, at the bottom of Park Hill. The last Harlow maltings was built in the 1870s in St. John's Walk, next to Harlow College and St. John’s Church. During World War II it was converted by the de Havilland Aircraft Company into a machine shop, and then lay derelict for many years until it was bought by Memorial University of Newfoundland in 1968. After conversion by local architect John Graham it became the main building of the University's Harlow Campus.

Chaplin's Brewery operated between 1848 and 1926. It began brewing in Fore Street in 1897 and its chimney dominated the western skyline of Harlow for many years. The 1851 Census shows that Thomas Chaplin was a man of some standing. He employed 12 men at the brewery, and 11 men on his 300 acres of farmland. Some of this was at Chippingfield, rented from the Rev. Joseph Arkwright. The brewery supplied many of the local pubs. In 1933 the now-disused brewery was taken over by Windowlite Limited, makers of a new type of wire-mesh-reinforced plastic sheeting. It was originally intended for use in greenhouses and conservatories, but during the War it was widely used to replace windows blown out by German bombing. The brewery/factory buildings and the manager's house survived until 1969 when they were demolished to make way for the houses of the Seeleys estate.

Deards' Industries

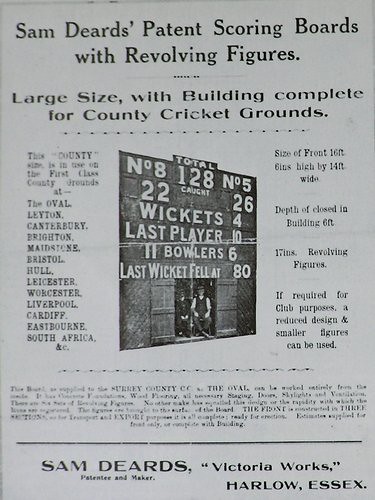

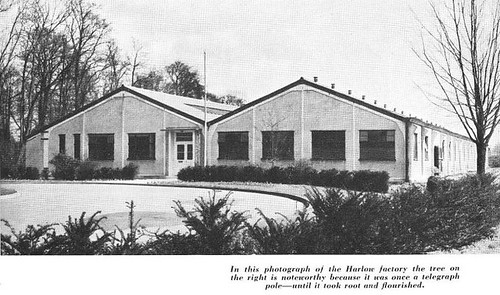

One of Harlow's best-known 19th century citizens was Sam Deards, whose accomplishments remind us that the wealth of Victorian England did not all come from the big cities. Deards was a pillar of the local community, serving as a member of the Fire Brigade for 35 years, and Captain for 30 of them. He was also a very successful inventor and entrepreneur. He was apprenticed into his father's plumbing and glazing business, but soon branched out on his own. Among his inventions was a machine to make building blocks using the clinker waste from the coal-fired power stations in the Lea Valley. Another was the first successful English mechanical cricket scoreboard. The Marigolds Cricket Club was founded in 1774. Its grounds were in High Street, behind the Fire Engine House, and it was here that Deard’s score board was first tried. It proved so successful that it was widely adopted throughout the U.K. Deard also developed a novel method of installing glass panels over large areas of roof. His 'Victoria Dry Glazing' method was used to roof Liverpool Street Station in London, the Colonial and Indian Exhibition Hall in South Kensington, and the Crystal Palace when it was moved from its original site in Hyde Park to Sydenham in 1852.

A London newspaper story entitled 'An Easter Egg for Harlow', published on 1 April, 1904, reported that Deards had been awarded a £10,000 contract by HM the King's Admiralty for the roof of a new factory. He had already put a new roof on the gun mounting stores at the Royal Dockyard at Portsmouth, and the Admiralty were so impressed with the 'excellence and economy' of this roof, both in manufacture and maintenance' that they awarded him this large new contract. The story enumerated the material that would be required: 10 miles of steel glazing bar, 20 miles of 12 inch wide glass sheet and 100 tons of lead to prevent rusting of the steel bars, and for flashings.

River’s Nursery

Many Harlow residents were employed at River's Nursery in Sawbridgeworth. Founded by John Rivers from Berkshire in 1720, it became one of England's largest and most successful nurseries, employing more than 2,000 people at its peak in the mid 19th century. Many of the workers lived in Harlow. This was no ordinary nursery. It specialized in providing garden stock for large houses with estate gardens. Always a family-owned and run business, it was extremely progressive. Correspondence with nurserymen all around the world made possible a collection of foreign and domestic plant varieties unrivalled in England. Charles Darwin made use of its research collection during the writing of The Origin Of Species. When the tax on glass was removed in 1849 it became possible, for the first time, to build glasshouses on a large scale. Rivers designed glasshouses for some of the most important estates in the country, including Audley End, where the 1856 glasshouse has recently been restored, and stocked with plants supplied by the Rivers gardens. The coming of the railway made it easy to ship their fruit trees, which came planted in huge pots, all over the country.

The firm made use of the new hothouse growing environment to develop whole new ranges of fruit cultivars, including the Thomas Rivers apple that is now extremely rare. The family always had a special fondness for experimentation with citrus fruits, and this was to serve the world well. In the late 19th century, American oranges were flourishing in Florida, but these varieties did not do well when transplanted to California. In 1876 the third Thomas Rivers sent a number of young plants to California and one of them, Valencia Late, proved satisfactory and laid the foundation of the citrus industry in that state.

The number of large country houses with gardens began to shrink after about 1900, and the country house was in serious decline by the 1930's. This caused the nursery to cut back on the scale of its operations. Then the range of varieties had to be cut dramatically during the Second War because of regulations which severely limited the amount of heating that could be provided in the greenhouses. In the post war era competition from overseas sources made the operation increasingly unprofitable, and after 265 years of operation the nursery was closed in 1985. The land was sold to a medical group and a private hospital, the Thomas Rivers Medical Centre, was opened in 1992. The surviving gardens are being maintained by a charitable trust. The story of the nursery is told in a book published in 2010, and available at The Museum of Harlow.

Spirella

The Spirella Company of Great Britain rose to prominence because of the invention in 1904 of the revolutionary aluminum corset stay, which quickly replaced the traditional whalebone one. It built plants in Niagara Falls (both New York and Ontario), Oakland, California, Malmo, Sweden; Copenhagen, Denmark; Berlin; and Letchworth Garden City in Hertfordshire where a major factory dominated the town for many years. In the late 1950s it transferred the production of brassieres to a small factory in Harlow, just north of Harlow Mill Station.

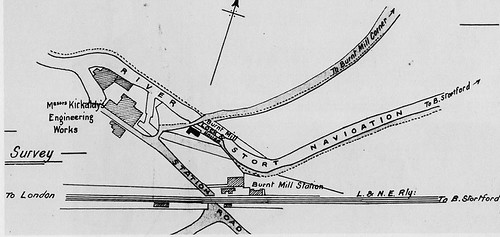

John Kirkaldy’s Burnt Mill Engineeering Works

In the 1880s John Kirkaldy moved his heavy engineering works from a Thames-side location in Poplar, east London, to a derelict flour mill on the site of the mediaeval Abbey mill at Netteswell. The principal output of the factory, the first heavy industry in the area, was evaporators, condensors and distillers. The original workforce of 200 men was enlarged during the Great War by many women to handle the demands of the Admiralty for equipment to desalinate seawater for the Royal Navy as well as the navies of Japan and Brazil. After the war the company diversified into the manufacture of machinery for the freezing of meat, but this wasn’t sufficient to maintain its operations and it closed in the 1930s. All but one of the factory buildings were demolished. The surviving building now houses the Harlow Outdoor Pursuits Centre, just west of Harlow Town station.