Sir Frederick Gibberd and the Design of Harlow

"Harlow was one of the first, and most successful, of the new town projects, being both relatively uncontroversial and unusually unified and architecturally distinguished in its physical plan" (Aldridge, 1966: 32).

"Harlow represented a particular synthesis of Englishness and Modernity. It combined radical ideas of collective living with local vernacular details, to forge a distinctive 'civic modernity' that for some was a successful reconciliation of Modernity and tradition, yet for others represented a trampling on English traditions. Retrospectively, Harlow has been described as exemplifying a form of modern planning in which social bettment was to be secured through the creation of an aesthetically-pleasing and rationally-ordered townscape, and hence as an example of a townscape whose form is steeped with the motives, economies and dreams of the 20th Century." (Hubbard, 2010: 407).

It is one thing to designate a new town. It is quite another to build it. The site chosen for Harlow New Town had little to offer. The only good road was the A11, the London Road. All the rest were narrow, often unpaved country roads, some of which have survived as cycle tracks. Water supply was a vexing question because Essex is a notoriously dry county. The Herts and Essex Water Company had reserve water for only about 3,000 houses. The Stort was about 50% sewage effluent, and this had to be cleaned up at the same time that a solution was found for the disposal of a vastly increased amount of sewage. Without employment, the goals of the New Town could not be met, but industry was not keen to relocate there, partly because the only access was through the east end of London and partly because the London and North East Railway had a very poor reputation. Despite these drawbacks and the obvious challenges they posed, the site was approved, the land acquired, and work on the town began.

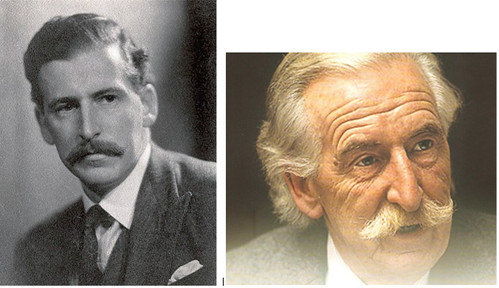

Harlow has the distinction of being the only one of the New Towns in which the master planner lived in it for the entire period of its development. Sir Frederick Gibberd, who has been described as ‘Britain’s leading architect-planner of the era’ (Alexander, 2009: 120), lived in Harlow from 1947 until his death in 1984.

The planning and building of Harlow was a heroic and idealistic endeavour that must be considered in light of its original intentions and the serious economic constraints under which it was born. It should not be evaluated in light of later criticisms that some of the basic principles upon which the plan was based were misguided, nor in light of modern attitudes towards housing design.

A principal goal of the New Town programme was re-house some of the people who were to be displaced from London and other towns in the South East of England in genuine, well-designed communities, with good services and amenities, while protecting and where possible enhancing, environmental quality. More than a half-century from now, our current planning orthodoxies may turn out to be no better than those adopted and practiced by Gibberd and his collaborators. The contemporary push to apply ‘Smart Growth’ principles and other new urban design ideas are just as likely to lead to the creation of places that fail the criteria of meeting future needs as the New Towns are said to have done. But that doesn't diminish the significance of what was accomplished in Harlow, and elsewhere, under the New Town programme.

Harlow, like all the other New Towns, suffers from the unintended side effects and unanticipated social and technological changes that made obsolete or impractical some of the original design decisions. Nobody in 1947 could have predicted that car ownership, much less multiple car ownership, would become the norm; that cycling would so completely disappear from the stable of journey-to-work options; or that television and then the Internet would reduce, and then eliminate the desire and need for communal entertainment.

Gibberd intended Harlow to be an outstanding example of the comfortable marriage of town and country. It was to be a town, not a rural village, but with lots of well-integrated open space to separate residential neighbourhoods and commercial zones. In spite of that, critics later said that its density was too low. But the economics of building a town on previously agricultural land made possible the relatively lower densities that many people wanted. And, given the Garden City lineage of the New Towns, it isn’t surprising that the presumed health benefits of open countryside would be incorporated in their design.

In 1953 Gordon Cullen and J.M. Richards published articles in the Architectural Review complaining about the ‘prairie planning’ of new towns in general, and of Harlow in particular. For these critics the low density and the basic landscaping plan, based on Gibberd’s treasured ‘green wedges’, meant that Harlow wasn’t a town at all, but merely a group of suburban estates separated from each other by functionless green space and large-scale roads. For them, Harlow was no different from the sprawling inter-war suburban housing estates developed by the London County Council. Although Harlow had the country’s first housing tower block (The Lawn, 1950) most of the town’s housing was made up of conventional two-story terrace houses and low-rise flats. Perhaps that’s why Le Corbusier, the champion of modern urban high-rise housing, refused to visit Harlow when he was in England for the 1951 meeting of the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne. But Gibberd was not only working on the basis of the housing densities proposed by the committee which set up the new town program, as low as four dwellings per hectare, compared to today’s standard of thirty or more, but also his own inclinations.

Gibberd was trained as an architect, and has a long list or major projects including terminal buildings at Heathrow Airport (1950-1969), and the Central London Mosque in Regent’s Park (1977). His most famous building is probably Liverpool’s Roman Catholic Cathedral (1967), a strikingly original structure popularly known as ‘Paddy’s Wigwam’. But his vision for Harlow incorporated much more than just the buildings and roads. He recognized the importance of context, and encouraged the emergence of landscape architecture as a specialty in its own right. The garden he created around his home east of Harlow on the banks of the River Stort is considered one of the best examples of the 20th century garden in the country.

Gibberd worked with landscape designer Sylvia Crowe to create a genius loci, or sense of place that would meet Ebenezer Howard’s vision of a union of countryside and town. Dame Sylvia, who was landscape advisor to the Harlow Development Corporation for 26 years from 1947 to 1973, added mounds and hills to the previously flat landscape using the material excavated during construction of the New Town. She was also responsible for the landscape design in the majority of the residential areas, and designed play spaces, open recreational areas and the settings for many of the industrial buildings.