Industry in the New Town

A principal goal of the New Town strategy was that each town would be self-contained in terms of employment and the provision of services, and socially-balanced. To accomplish this, Development Corporations had to attract employers, and to make them as varied as possible, so that employees with a variety of trades and skill levels would be attracted to the town. Significant financial and other incentives were offered to companies, especially large ones, to help achieve this goal. The incentives were particularly important in the case of Harlow which was not considered a desirable place for industry, largely because of poor communications. The Great Eastern Railway was reputed to be the dirtiest and least reliable line in the country, and the main road routes out of London went through some of the most dilapidated suburban areas in the region. Another important factor was that Essex had an undeserved reputation as a flat and featureless county, completely lacking in character.

The Corporation wasn’t interesting in trying to attract heavy industry, nor any industries that used a lot of water, because Essex is a notoriously dry county. Nor did they want to became a one-industry town. The plan was to attract a variety of light industrial firms, particularly those in sectors thought most likely to have significant potential for growth, with no one firm employing more than 10 percent of the available workforce. The emphasis was to be on engineering and electronics. The Corporation’s recruiting efforts were so successful that in 1973, electrical engineering firms employed 36 percent of the town’s workforce.

Employers were given the absolute assurance that housing would be provided for all of their staff who wished to move. Most companies wanted the Corporation to provide suitable, custom-designed buildings, and it was happy to do so, and then lease them for 99 years. The Corporation politely said ‘no’ to any business that wanted to purchase the freehold. To attract smaller employers the Corporation built small, modular premises that were available for lease in varying sizes. Many of these units are still in use along South Road in Templefields and in parts of The Pinnacles.

In its early days, the Harlow Development Corporation successfully attracted some large employers. They included Gilbeys Distillers, United Glass, Longman’s Publishing, Revertex (synthetic resins), Schreibers Furniture (with 2,500 employees), Johnson Matthey Metals, and Smith Kline Beecham (pharmaceuticals). A.C. Cossor employed 1,800 people in 1980, producing Britain’s first VHF radios.

Most of the pioneering companies have gone. The United Glass factory became a warehouse. Gilbeys, which had moved its distillery to Harlow from Camden Town in 1962, closed it in January 2000 because it couldn’t be modernized and enlarged on its constrained site. The building was demolished and replaced by a Sainsbury’s superstore. The original Longman House, designed by Frederick Gibberd and built in 1968, was replaced with a new building designed by Terry Conran for the Pearson Group in 1994. Pearson moved to new premises in KaoPark in 2017, and their old building is being converted to Edinburgh Gate which will contain 253 studio, one- and two-bedroom flats. Schreribers, Revertex, the Dorstel Press, Johnson Matthey, and Smith Kline Beecham have all gone. But Harlow continues to attract new employers because of the continued expansion of Stansted airport and its proximity to London.

Nortel and Kao Park

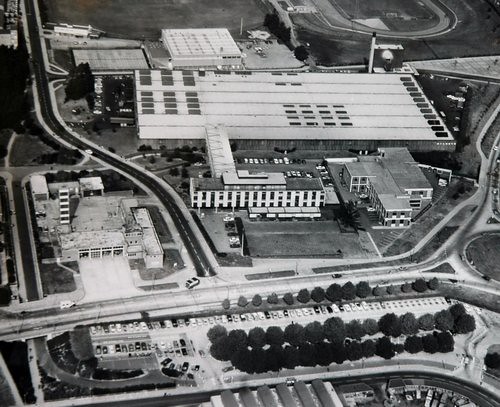

Probably Harlow's biggest industrial coup was convincing the Standard Telephones and Cables company, later Telecommunication Laboratories (STL) to locate in the New Town. The company started on a very small scale, producing crystals in a small factory. But it expanded rapidly, and when its application for a greenfield site in Hertfordshire was rejected in 1956, the company accepted the Corporation’s offer to permit the construction of a large plant on a site carved out of the company’s sports area between Old Harlow and Potter Street. The site had a long history of technological innovation. It was here that Alec Reeve developed the long-range navigation system called Oboe in the 1940s. The workforce quickly grew to 1,000 people.

In the 1960s one of STL's employees was Charles K. Kao who published a paper in 1966 explaining how data could be transmitted through pure glass strands. This pioneering work made Harlow the birthplace of fibre-op technology and won Kao the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2009. In 1991 STL became part of Bell Northern Research, which morphed into Northern Telecom, and then into Nortel. This Canadian firm, founded in Montreal in 1895, employed 8,000 people in Harlow before its cataclysmic collapse in 2009. This was the largest corporate bankruptcy in Canadian history. The site lay mostly derelict for several years, but is now being developed as KaoPark, in honour of Sir Charles Kao, as a ‘next generation campus’ for the integration of business and innovation. The first tenants were Arrow Electronics and Raytheon U.K. they have since been joined by Pearsons Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS Trust, Virgin Health Care and NHS Hertfordshire Partnership University.