This hugely acclaimed Cannes Palme d'Or-winning opener will set you up for the year. When it works, film is so great at drawing us into courtroom-psycho dramas, because we, like a jury, are in the dark, trying to uncover the truth from a muddle of conflicting evidence. Such is the case here as we are witness to the prosecution’s claim that Sandra, a successful novelist, has killed Samuel, her less than successful writer-husband. At the centre of this drama is their son Daniel who is legally blind, and therefore can only, like us, cast his judgement based on instinct and the evidence presented before him. Sandra remains a mystery wrapped in several layers of linguistic skill and charismatic confidence. This is one of the great whodunnits of our time—a sheer and exhilarating pleasure from the word go/allez.

MUN Cinema has already shown one of Kaurismäki’s films in what is now a quartet called “Proleteriat.” FALLEN LEAVES explores the same social issues as the first three, but it focuses on the redeeming possibilities of love and hope. What could be cuter than meeting someone at a movie theatre, sharing food and fresh perspectives. So it is that Ana meets Holappa and gives this hapless romantic her phone number, only to have it whisked away by the wind. To say more would be to ruin the joy of expectation and desire. If you hate capitalism you’ll love this film that one critic has called “perfect” for its immaculate depiction of the human condition in all its struggling sodden glory.

This film lifted everyone full up last year at Sundance. Composed as a series of tales within tales, it features Leila, a gay Iranian-American girl with nine brothers. She is a lively free-spirted filmmaker who parties hard and in some sense pays for it after a particularly abandoned night. Her disapproving mother has her own stories to tell, and eventually, and shockingly, we learn more about her past in Iran and what made her who she is. Essentially a forgiving story of a mother-daughter relationship, the film is also a glorious celebration of—wait for it—80s dance music and cultural difference. Bring it on.

Sure, it’s long, but it’s also a wry comedy that wants to draw you into its languorous pace and meta-storytelling—that is, the director often winks self-consciously at his own unconventional take on the heist genre. A couple of ordinary guys, bored with life and their jobs, do a bank job. That’s the plot in a nutshell. It happens almost by accident, but it happens. And because we have seen so many bank-robbery films we think we know what will happen next. But Argentine filmmaker Moreno foils us at every potential point of predictability. The plot thickens, slows down, goes off in left field, slows down again, and so before you can say existentialism you realize you are experiencing a naturalistic experiment, not a Hollywood formula.

Another Sundance triumph, SCRAPPER is a coming-of-age story featuring 12-year-old Georgie. Her mother dies, leaving Georgie to her own scrappy resourcefulness, stealing bikes, evading school, and inventing new ways to escape responsibility. Out of the blue—and over the fence—comes long-lost dad, all set to raise Georgie, even with his own severe case of arrested development. What evolves is the fascinating dynamic between father and daughter, as each learns from and teaches the other some new tricks and hard lessons. This is a highly entertaining debut by a filmmaker who is going places.

Based on the Holocaust novel by Martin Amis, this superb and controversial film will stay with you long after the credits roll. Rudolf Höss is a hard-working family man, devoted to his wife, children, and their bucolic home in the countryside. He is also a Nazi living on the other side of the walls of Auschwitz where he works. As with several famous representations of the Holocaust it is what we do not see that informs the tingling horror of history—in other words, the banality of an evil that lives comfortably side-by-side with grotesque crimes and unspeakable suffering. UK-director Glazer always delivers, as MUN Cinema has literally shown time after time. THE ZONE OF INTEREST is next level, though, as much about the Holocaust as it is about 2023.

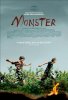

Remember the brilliant cinema of Kore-eda’s Shoplifters? Well, here we have another equally smart study of a broken family, this time shot from three different points of view. The monster of the film is young Minato whose single mother and frustrated teacher comprise the other two perspectives of the narrative. This is Rashomon with a fifth-grader at the centre. Childhood isn’t for sissies, and MONSTER underscores the challenge of being constantly misunderstood, but the film also asks us to determine where the truth lies—a task for the enlightened adult film spectator, no doubt.

For more information please contact

Noreen Golfman

ngolfman@mun.ca

cinema@mun.ca