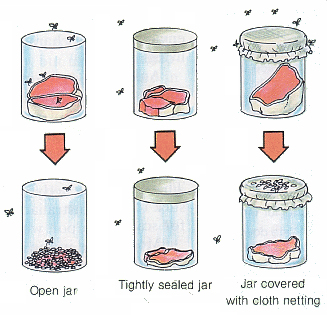

Redi experiment

(1665)

As late as the 17th century, some

biologists thought that some simpler forms of life were

generated by spontaneous generation from inanimate

matter. Although this was rejected for more

complex forms such as mice, which were observed to be born

from mother mice after they copulated with father mice,

there remained doubt for such things as insects whose

reproductive cycle was unknown. [An important step was the

documentation by Maria

Sibylla Merian (1647 - 1717) of the stages of

metamorphosis in butterflies].

To test the

hypothesis, Francesco Redi placed

fresh meat in open containers [left, above]. As expected, the

rotting meat attracted flies, and the meat was soon swarming with

maggots, which hatched into flies [left, below]. When the jars

were tightly covered so that flies could not get in [middle, above], no maggots

were produced [middle, below]. To answer the objection that the

cover cut off fresh air necessary for spontaneous

generation, Redi covered the jars with several layers of porous

gauze [right, above] instead of an air-tight cover. Flies were

attracted to the smell of the rotting meat, clustered on the

gauze, which was soon swarming with maggots, but the

meat itself remained free of maggots [right, below]. Thus

flies are necessary to produce flies: they do not

arise spontaneously from rotting meat.

Redi went on to demonstrate that dead maggots

or flies would not generate new flies when placed on

rotting meat in a sealed jar, whereas live maggots or flies

would. This disproved both the existence of some essential

component in once-living organisms, and the necessity of fresh

air to generate life.

Note that is unnecessary to observe or even

imagine that are such things as fly eggs, nor

does the experiment prove that such exist. Redi's experiment

simply but effectively demonstrates that life is

necessary to produce life. Redi expressed this in

his famous dictum as "Omne

vivum ex vivo" ("All life comes from life").