The Whale Man

As an animal behaviourist, Dr. Jon Lien had studied whales, but he had never tried to disentangle one from a fishing net before.

And yet there he was in the fall of 1978, in Trinity Bay, leaning over a gunwale and cutting lines to rescue a massive humpback whale from a gillnet.

Dr. Lien managed to free the whale that day, and he would go on to learn that whale entrapments were becoming more and more common in the coves and bays around the island of Newfoundland.

Whales caught in fishing gear could starve or drown. And inshore fishermen were suffering serious financial losses because their expensive gear was being severely damaged or destroyed entirely.

Setting out to save the lives of whales and the livelihoods of fishermen, Dr. Lien received a small research grant and established the Whale Research Group and its Entrapment Assistance Program in 1979.

The Entrapment Assistance Program offered fishermen a phone number and promised to respond to reported entrapments within 24 hours.

By 1983, the program had trucks and equipment ready to respond at a moment’s notice. Dr. Lien told the Western Star that it was “kind of like a fire department operation.”

Graduate students and wildlife enthusiasts from around the world began travelling to Memorial for the chance to rescue marine animals alongside Dr. Lien, who through constant vigilance would come to be known as the Whale Man.

Dr. Lien was born in landlocked South Dakota in 1939. He earned his doctorate at Washington State University. Though he had competing job offers from universities in Montreal, Hong Kong and Chile, he accepted a position at Memorial in 1968 and settled in Portugal Cove.

On a six-acre plot of land, he constructed his house by recycling lumber from the old Bowater Salt warehouse on the southside of St. John’s and with hardwood flooring from the offices of the shuttered Bell Island mine. In his backyard, he started one of the first organic farms in the province.

His work at Memorial first involved the study of sea birds, but the Whale Research Group would eventually become the primary focus of his esteemed career.

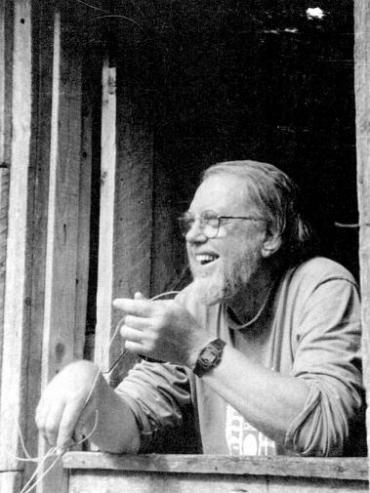

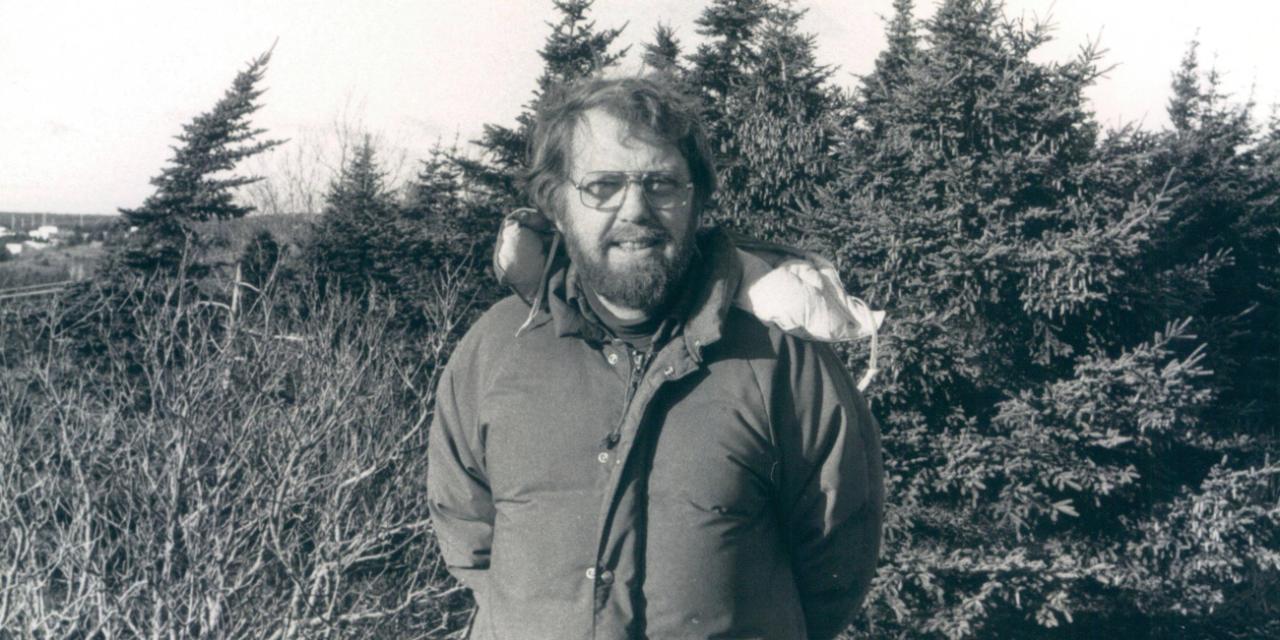

Dr. Jon Lien circa 1984. Photo from Decks Awash.

Although the media often referred to the issue of entanglements as “the whale problem,” Dr. Lien understood that what was happening couldn’t be attributed to a single species. Something was changing within the ecosystem. As caplin stocks began to decline, whales were coming further inshore to feed, leading them directly into the path of fishing nets.

While he continued to respond directly to entrapments and pioneered techniques for releasing trapped whales that are still used around the world today, Dr. Lien also searched for other solutions.

Working with engineers at Memorial’s Centre for Cold Oceans Resource Engineering, he helped to develop devices that would periodically emit a pinging noise. These pingers could be attached to fishing nets to divert whales away from danger.

The devices worked, and when harbour porpoises were being inadvertently trapped in the waters off the coast of New England, Dr. Lien travelled along the eastern seaboard to help fishermen make pingers by using inexpensive parts readily available at automotive and hardware stores.

His fame grew. He travelled to numerous international conferences and speaking engagements to share his knowledge with scientists and conservationists. He helped guide and worked with Canada’s national parks and marine protected areas and a host of conservation projects.

He was awarded the Order of Canada, the Order of Newfoundland and Labrador, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation, the Keyes Award for Research and Conservation and the World Environment Day Award, along with many other accolades and honours.

Dr. Lien died of heart complications in 2010 at the age of 71.

Between 1978 and 2002, he managed to personally save the lives of over 500 marine animals.

The devices and techniques he developed saved countless more.

After working to release a whale, Dr. Lien was known to remain on site to help fishermen repair their nets, learn their stories and think about new ways to help.

He was admired as an innovator within the scientific community and beloved amongst those who made their living on the sea.