Human karyotypes: 2n = 48 or 46?

Early studies of

the human karyotype simply stained chromosomes

within cells with Giemsa and "squashed" them between the cover slip and

slide. Most cells were not at the proper mitotic phase for

chromosomes to be observed, and chromosome separation was

poor. The exact count was uncertain: most workers accepted

the number 48. The

breakthrough came in 1952 (left) when a technician in the

lab of TC Hsu

accidentally substituted distilled water for the normal

saline solution used in washing the cells just before "squashing". This "hypotonic" treatment

caused the cell nuclei to swell, and allowed the chromosomes

to separate before squashing. A further refinement was "dropping" the cells

onto the slide at arm's length, which caused the nuclei to

burst on impact, further separating them (middle). Finally,

the use of a plant spindle-poison Colchicine allows

chromosomes to be arrested at mitotic metaphase,

during their maximum state of compaction [right]. These

experiments allowed JH Tjio & A Levan

(1956) to establish the human chromosome number as 2n = 46 chromosomes: the

"24th" pair turned out to be a pair of satellites on

the ends of another pair.

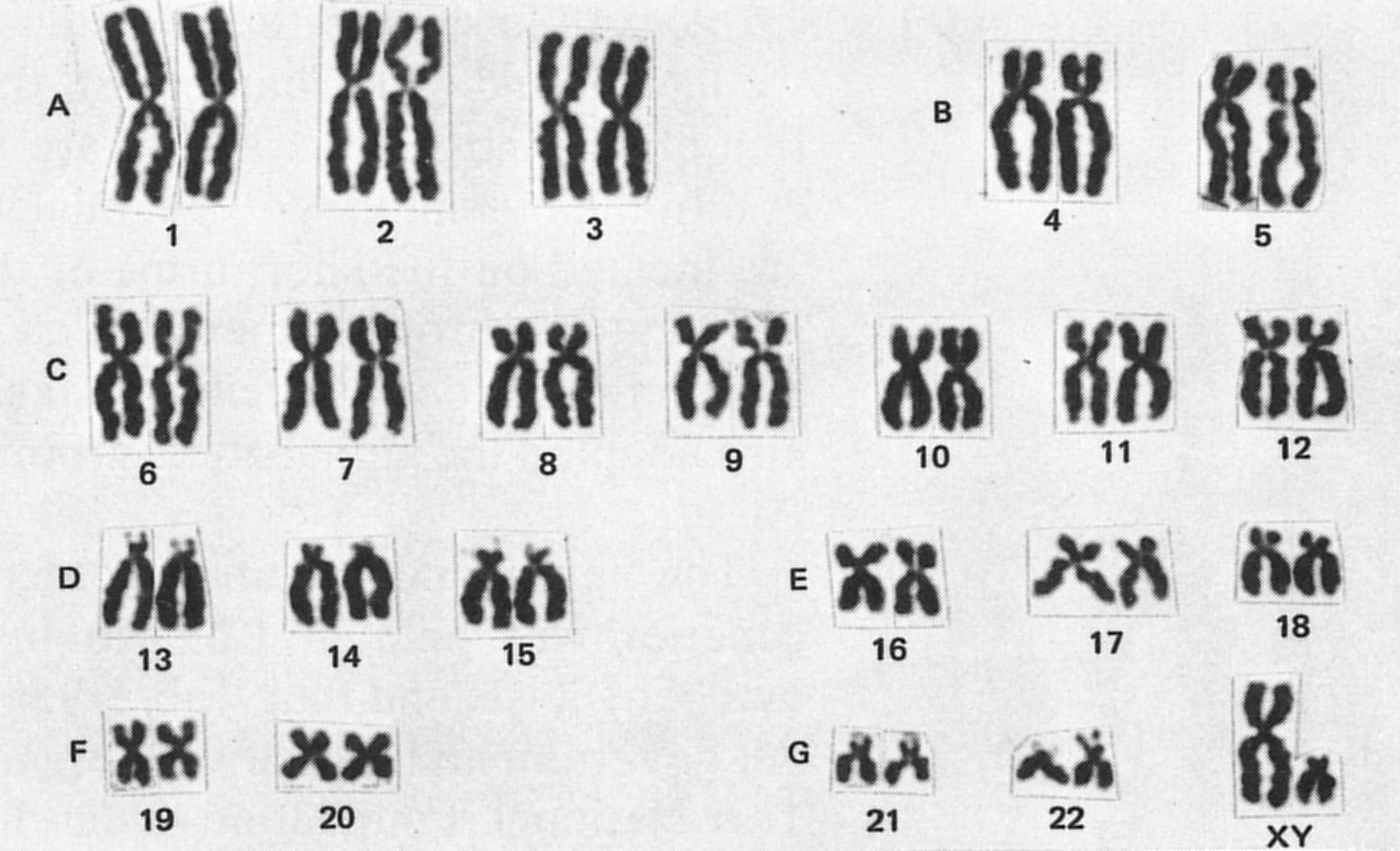

Classification of chromosomes into seven groups by size and relative centromere position established the so-called "Denver System" (right) in 1960. Chromosomes within groups B - G were not readily distinguishable from each other. The X chromosome is in the C group, and the Y is in the G group: males are recognizable by five small G-type chromosomes. Modern banding techniques allow each chromosome in the karyotype to be distinguished individually.

Classification of chromosomes into seven groups by size and relative centromere position established the so-called "Denver System" (right) in 1960. Chromosomes within groups B - G were not readily distinguishable from each other. The X chromosome is in the C group, and the Y is in the G group: males are recognizable by five small G-type chromosomes. Modern banding techniques allow each chromosome in the karyotype to be distinguished individually.